|

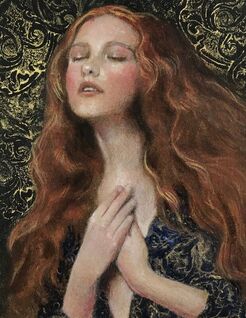

Love, an unchartered territory, for it creates a whirlwind of conflicting emotions that quandary the soul, and perplexes the mind. Riddled, we are, with a sense of idealisation that begins from birth, and steers us through life, until our formidable last breath.

We begin life with an intense desire to experience love, for intrinsically, we are pleasure-seeking animals, and go to extremes in the name of idealised love for the soothing it brings us. We are, however, merely consumed with layers of demands and expectations, that swing in the prism of duality, that sways us across the labyrinth of polarised extremes. Filled, we are with unconscious drives and motivations inherited by societal structures, norms and narratives. As the tribal urge for conformity to societal values takes precedence for external approval and validation, “love” takes its toll on our life, and we become laboured in pursuit of it. The idealisation of love, which according to Freud is rooted in narcissism, departs immensely from the actual experience of love itself. So, perhaps, the option to sublimate our idealised attachments and discomforts, may serve as a remedy to lessen the cruel, destabilizing and dangerous illusions of love. Unbeknown to our human sensibility, exists a hidden realm of the unconscious, which meticulously plays out one’s repressed desires, projecting the inherently hidden drives upon another, in pursuit of “love”. The unconscious is riddled with inferiorities, inadequacies, despair, jealousy, resentment, possessiveness, and scrupulous attachment upon others, for the purpose of its own gain. It cares not for another, for the instinctual self satiating drives motivate its behaviour. The sublimation of one's animal drives, rests upon the individual’s quest for self-awareness and self-inquiry. To experience this transcendence, the individual is set forth to decode his/her subjective definition, and rationale, for seeking relational love, external to self. In a symposium, Plato describes a dialogue regarding the nature of romantic love. He provides the myth for why mortal humans seem to crave love from another. He contends that in the beginning there were androgynous spherical beings, consisting of half man, and half woman. In an act of realisation, Zeus, king of the gods, severs each spherical being in half. From this, rises the story of humans, born incomplete, in pursuit of its other half to complete itself. This metaphor plays upon the human quest and motivation in pursuit of love, ever seeking the attainment of one’s object of desire to feel complete. Much unrealistic idealisations arises from this metaphor, further reinforced within the human psyche by popular culture, creating momentum, within the human quest for perfect flawless love. Further afflicting confusion upon the mismatch of one’s reality, to the idealised concept of love. The idealisation of love, as a means for completing oneself, sells, for it tugs at the very lack that resides within the realms of our human unconscious. Our patriarchal, parasitic and capitalistic societal structures feed upon this lack, by selling idealised illusions of love and pleasure to the delusion of its love starved consumers. Around the world, the quest for love has driven humans to do extraordinarily dramatic things, from waging wars, to building shrines, acts of terrorism, murder, suicide to creating markets, and agencies for procuring and selling sex. Love is complex, but in our contemporary world, love has also become a commodity for consumption. We’ve never been so globally connected, yet so deeply disconnected through excessive addiction to social media, digital devices, and over consumption of porn, sex, and dating sites. On these digital platforms, one can anonymously select from a vast menu of pleasurable commodities. Capitalising love has played its part in nuancing love further within western societies, and is certainty reforming dynamics in respect of intimacy and desire. Our capitalistic steered society continues to seduce our attention outwards in pursuit of love, inflating “love” as a commodity for consumption. Across all timelines, cultures and even within the psychoanalytic movement, humans have attempted to reconcile the notion of sex with love. Like all aspect of mating and reproduction, cultural norms vary in its expressions of love. In the west, sexual desire and love, exists in tandem, superseding the notion of marriage as a means of retaining one’s lineage and status. The enlightenment period may have birthed an era of romanticism, which created cultural shifts towards infusing love within human consciousness. Once predicated upon the notion of economic necessity, marriage became redefined as a commitment of love, and weighed its longevity on the premise of intimacy, passion and desire. Whilst romanticism sells commercially, it’s application within long-lasting relationships stand to scrutiny. The cultural aspect of love shall rest here, for it is far too nuanced to address in this essay, and its connotations vary across continents and timelines. For this essay, the focus leans upon the western notion of love and desire, for this in itself shall serve as a multi-layered spectrum to decode, as to why love is sometimes viewed along with hate, fear and cruelty, as a destabilizing force in both our personal and social life. From an antiquity perspective, the ancient Greek Philosophers had made some sense of man’s destiny in respect of love and desire. They believed one had to overcome his animal nature before evolving to be human. According to Aristotle; “desire must obey reason”. The Greek philosophers claimed that whilst it is within human right to use pleasure and desire, one must be cautious not to be carried away by it. “Pleasure is a force liable for excess that requires control and regulation.” The Greek philosophers referred to self-restraint as “Chrésis a phrodision”, relating to one’s sense of “prudence, reflection and calculation” in respect of desire. Self-control and continence ruled over pleasure and desire, and this led to “enkrateia”which translates as self-mastery. To the Greek philosophers, matters pertaining to pleasure, and love, are contingent on a battle for power, an internal battle that requires attention. Exerting power and domination over one’s desire was regarded necessary, in creating and sustaining a morally motivated society. It was the responsibility of individuals to construct a relationship with his inner self that was of “domination-submission, command-obedience, and mastery-docility”, in pursuit of self-regulation, prudence and moderation. Such qualities were deemed as high virtues to be mastered by all humans. Today, fantasies, desires and idealisations are regarded by some psychoanalysts as a necessary, and healthy, phase of adult-human life. It’s proposed that through meticulous effort in reconciling one’s narcissistic idealisations, the individual may journey in to the realms of self-mastery, and rise above the polarised dance between love and hate. However, in our modern world, we are not guided by any sense of authority, as to how one may journey through this dance. Rather we are scuttled by cultural norms to find “true love” without any form of initiation in to learn what love is, before we set upon a quest to find it. In remanence to Greek philosophers, Freud also states “a man who has owned his way to a state of knowledge, cannot properly be said to love and hate; he remains beyond love and hate, for he has investigated instead of loving”. Perhaps transcending love and hate is the cure for the ailments we encounter in search of this unformidable force? The force that evokes bravery, inspiration, bliss, motivation and madness. The polarity spectrum that exists in the name of love swings far and wide. Thus, transcending our animal nature through self-knowledge, as the Greek Philosophers and Freud denoted, may well be the antidote in rising beyond the polarity dance. To truly transcend love and hate, one must learn to sublimate the inner confinements of a self-obsessed, narcissistic, pleasure-seeking animal, in to a passionate quest to live an emotionally rich and creative life. For this perhaps psychoanalysis can illuminate, or further confuse our inquiry. In our postmodern, capitalistic society, where love, romance, desire and passion are idealised more than ever as means of production, can psychoanalysis really help us to decode our relationship to love and desire? Perhaps our capitalistic society places greater burdens on love between heterosexual relations? For Freud, a man in society represents the work of civilisation, whilst, woman represents the family and the interests of sexual life. As such, he believed, civilisation demands more libidinal resources of men than women. Thus, a man’s attempt to reconcile his finite energy between society’s needs, and the needs of his relationship, creates estrangement in the relationship. Whilst society has significantly evolved since Freud’s theories of femininity and masculinity, societal narratives and pressures continue to create tremendous tension, and estrangement between the sexes. The paradigm shifts, post first and second wave of feminism, led to women’s “liberation”, as it achieved major reforms in legislative rights for women in western societies. As a result, western cultures have seen an increase in women’s contribution within the workforce and the public sphere. Women’s contribution and leadership in the workforce, alongside juggling demands of parenthood in a patriarchal system, have also introduced new paradigms and tensions within heterosexual relations. Rise in divorce rates, and single parent families are inducing socio-economic tensions. These paradigm shifts are narrating what masculinity and femininity mean in context of 21st century, and how they relate to each other. Whether these contemporary waves of feminism such as the #Me-Too movement, further enslave or free the sexes in their quest to find love, power, and freedom, remains lucid. Outside the societal tensions; love remains laced with ambivalence, as well as wishes for dominance and submission, love is where fears of abandonment reside, where struggles of attachment and separation loom, and a place where fantasies of infantile dependencies and idealisations roam. Perhaps the idealisation of love and desire, are remanence of an earlier oedipal patterns and dynamic? Thus, let us further explore the Oedipus Complex as theorised by Freud 1910 in our quest to decode our human desire for love. Freud theorised that the oedipus phase is where a child’s unconscious sexual desire for the mother, evokes a deeply seeded hatred for the father. Thus, giving rise to complex emotions pending emotional reconciliation within the child. According to Freud, the realisation that the mother is unattainable sexually, results in fear of castration for boys, and penis envy for girls. Whilst Freud’s oedipal phase for boys follows a natural realisation regarding his love object, the model theorised for girls, remains somewhat incomplete, for Freud’s theory eludes that girls encounter indefinite inferiority complex, due to realising that they do not have a penis. Feminists such as De Beauvoir perceived Freud’s theory as an extension of his own misogynistic viewpoint, whilst later feminists including Juliet Mitchell (1974) viewed his theories symbolic to patriarchy in a phallic centric society. For Freud, Masculinity was the natural state for both sexes. He claimed that a girl retreats from masculinity in to femininity upon the fateful and unhappy discovery that she has no penis. Castration anxiety may explain how a young boy journeys to reconcile his perceived inadequacies in relation to the object of his desires. How the dyadic and triadic relations play out for him in his early childhood, may perhaps determine his ability to reconcile his contrasted emotions, in search for his confidence towards the of objects of his desire. In the case of penis envy, if understood metaphorically, in context of a phallic centric society, (in that a penis represents “power”), then this theory surely becomes applicable to both boys and girls, for it symbolises the deficiency in the power dynamic, that one may perceive in relationship to his/her objects of desire. In both Freud and Lacan’s accounts of psychoanalysis; the oedipal theory concludes that the mother, is both desired and dangerous, whilst the role of the father is the regulator of the child’s desire for the mother. Freud states that, childhood love is boundless; it demands exclusive possession, it is not content with less than all, and this demand, can only end in disappointment. In contrast to Freud’s notion of sexual pleasure as a primary motive, Melanie Klein points out the significance for the dual maternal relationship that exists between mother-baby, and of the aggression that derives from it, including feelings of guilt and reparation. In this way, love appears along with the emergence of depressive and aggressive position for the child. Klein positions the development phase upon the complex intimate and relational component that establishes motives and behaviours, and one that aligns closer to attachment styles. The Oedipus complex divides much of the psychoanalysis movement, but perhaps if the theory is taken as a symbolic derivative to power, one can begin to perceive the dynamic as a means of transgression and resistance against the power structures that stand in the way of one’s desires. Creating essentially, a tug of war between the individual, and the object of his/her desire. Freud’s notion that desire is dangerous and unattainable, reflects the need to sublimate the narcissistic aspects of desire. Essentially, individuals continue to play out the oedipus constellation all throughout life within different social structures. The “mother” becomes the metaphor for desire, and the “father”, becomes the authoritative obstacle that is to be overcome, or is to be sublimated in attaining one’s object of desire. How one reconciles his/her emotions in respect of the love object, including fear, envy, inferiority, jealousy and guilt rests upon the triadic and dyadic relationships held within the oedipal phase with the mother and the father. Thus far, we understand that psychoanalysis deeply concerns itself with human sexuality and the unconscious, and views both concepts as deeply intertwined between the feminine and masculine principles. In psychoanalysis, a person’s relationship with desire is believed to be formed through his/her sexuality, and the unconscious contains instinctual desires that may not have been realised, causing unresolved fears and emotions regarding the desire to be repressed. This repression causes angst in one’s ability to seek desire later on in adult life, unless of course, the pain and trauma within the Oedipal phase is examined and reconciled. According to Lacan; the unconscious castration complex shapes neuroses, perversion, psychosis and one’s inability to respond adequately to the needs of his/her partner in respect of sexual relations, nor address the needs of the child he/she has procreated. Therefore, taking us back to the fundamental oedipal complex as a primary source, where perceptions and limitations dictate human behaviour towards desire and love. Essentially, humans perceive intimate relationships in alignment to their unique oedipal journey. The feelings which compose the oedipal constellation like jealousy, guilt, rivalry is determined, and stimulated by desire, for desire is a source of human fuel in life. In essence, desire gives birth to creativity, for without it, much of life would not exist. We are born from the desire of our parents, we need to be seen by them, we have our own desires and, we have desires toward others, this is why, in every relationship, desire can be stimulating but also creates much conflict. Stephan Mitchell (2002) states; “the object of desire has enormous power, and vulnerability of the lover is proportional to the depth of love, the vulnerability and dependence to another threatens the integrity of the self. The conflict here is that our desires make us dependent upon another, and this dependency leads to aggression and fear for its loss or failure to accomplish the desire. In a mature relation, the feelings of love with capacity to contain one’s dependence and vulnerability toward another predominates comparative to aggression.” The extreme polarisation effect in dependency cause attachment and idealisation, which swings the pendulum towards aggression, suffering, hatred and fear. The Dalai Lama (1997) described the emotional landscape of desire in this way: "If you look carefully, everything beautiful and good, everything that we consider desirable, brings us suffering in the end". Lacan along with many Buddhist thinkers, agree that desire is defined as longing which can never be fulfilled. Fundamentally, our desires, whether they are aimed at bringing pleasure or power, avoiding pain or humiliation, express a longing to control others and the world, all desires ultimately disappoint us when we discover the limits of our control. Young-Eisendrath argues that certain desires must be defeated in order for transformative love to emerge, echoing the philosophy of the ancient Greeks. Love is a transition journey from the erotic object to the beloved person. Once again, we return to the idea that one is to sublimate the idealisations, narcissisms, traumas and expectations in order to attain the love that is untainted with the incomplete oedipal narrative. Love gets conflated with its near companions of romance, desire, idealization, admiration, and compassion. In order to feel truly loved, we have to feel authentically known and seen. true love is a developmental achievement, that must be kept distinct from its companions of desire and attachment. This introduces other concept such as the individual’s receptivity to express vulnerability and intimacy within the relational dynamic, and one’s ability to deconstruct love, attachment and desire. Love is the revelation to freedom. Perhaps Psychoanalysis teaches us to appreciate the nuances of love and desire, and one’s ability to take responsibility for one’s subjective projections, and interpretations in respect of personal and social relationships. One’s desire and idealisation for narcissistic control of another (in the name of love) must be sublimated with freedom for autonomy and self-expression. One is to be aware of the unconscious polarisation effects, influenced by idealisation, and seek the opportunity to resolve polarised dynamics that exists between; dominance-submission, abandonment-engulfment, attachment-separation, and dependence-independence, that play a part in every relationship. Perhaps Love is not only a feeling, or a state of being, nor an attitude, sexual desire, or attachment, but more than this, love is also power. There is no love without the initial idealised desire to satiate the narcissistic drive for power and control. From oedipal complex determining human attachment styles, psychoanalysis attempts to make sense of love, attachment and desire. Love is inevitably linked with loss, and in experiencing loss, one acquaints with a deep sense of grief and cruelty associated with one’s lack of power and control. The force of grief renders one powerless, by destabilising the very essence of one’s departure from his/her idealisations and fantasies. The journey to attaining love remains an illusionary force, impressed upon a capitalistic society, yearning and starved for love, freedom and power. Masquerading as love, the unconscious oedipal drives manifest as narcissistic attachments and control. The human desire for power and control ultimately creates a paradigm where love becomes viewed along with hate, fear and cruelty, as a destabilizing force in both our personal and social life. Paradoxically, this destabilisation also serves as fuel for creativity, which ultimately serves in advancing human life and civilisation. Essential for the evolution of our consciousness.

0 Comments

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed